Akcie společnosti Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ:TTWO) dnes klesly o 3,3 %, poté co společnost oznámila plánovanou veřejnou nabídku svých kmenových akcií v hodnotě 1 miliardy dolarů. Pokles odráží reakci investorů na potenciální zředění stávajících akcií v důsledku rozsáhlé nabídky.

Společnost Take-Two, známá svými populárními videohrami, uvedla, že všechny akcie v navrhované nabídce budou prodány společností. Kromě toho očekává, že upisovatelům poskytne 30denní opci na nákup dalších akcií v hodnotě až 150 milionů dolarů. Společnost hodlá čistý výnos z nabídky použít na obecné firemní účely, které mohou zahrnovat splacení nesplacených dluhů a financování budoucích akvizic.

Oznámení přichází v době, kdy mnoho společností zkoumá různé možnosti financování s cílem posílit svou rozvahu a financovat růstové iniciativy. Rozhodnutí společnosti Take-Two o potenciálním navýšení počtu akcií by jí mohlo poskytnout kapitál nezbytný k dosažení strategických cílů, ale bude to na úkor potenciální hodnoty akcií stávajících akcionářů.

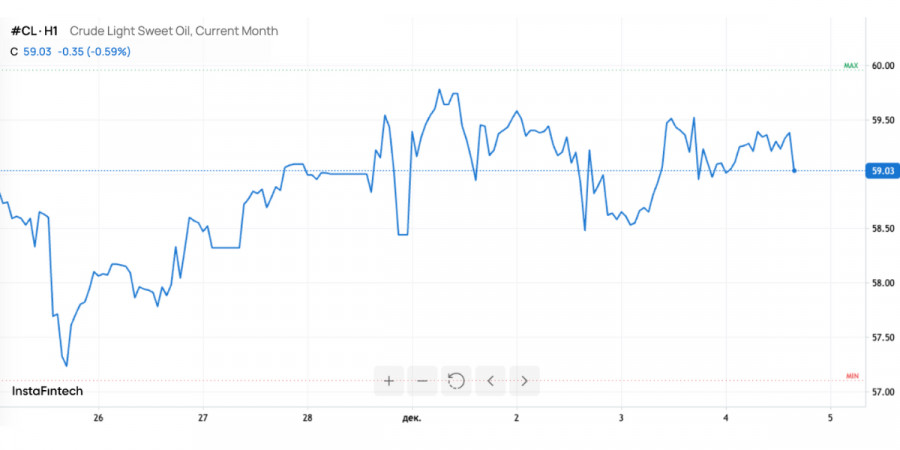

O mercado de petróleo voltou ao centro das atenções: os preços estão subindo, mas esse movimento não se parece com o início de um novo rali de commodities. O Brent segue consolidado em torno de US$ 63 por barril, enquanto o WTI permanece próximo de US$ 59, ambos dentro de uma faixa relativamente estreita. Ao mesmo tempo, o cenário segue tenso: por um lado, os riscos geopolíticos estão aumentando e as preocupações com possíveis interrupções no abastecimento ganham força; por outro, os fundamentos apontam para estoques confortáveis, oferta elevada e demanda fraca.

Como resultado, o mercado opera em um estado de equilíbrio constante: notícias de curto prazo adicionam um "prêmio de risco" aos preços, enquanto fatores estruturais rapidamente atuam no sentido contrário. Cada vez mais, analistas apontam a faixa entre US$ 60 e US$ 70 para o Brent como o intervalo no qual o petróleo pode permanecer preso por um período prolongado, a menos que ocorram mudanças significativas — seja do lado da oferta, seja do lado da demanda.

O movimento de alta mais recente foi desencadeado pelos ataques à infraestrutura petrolífera russa e pela paralisação simultânea das negociações de paz. Esses eventos intensificaram imediatamente as discussões sobre riscos de interrupção no abastecimento e levaram alguns participantes do mercado a encerrar posições vendidas e comprar petróleo como forma de proteção.

Um caso simbólico envolve o oleoduto Druzhba, por onde o petróleo russo é transportado para a Hungria e a Eslováquia; o ataque mais recente foi o quinto desse tipo. Tanto o operador quanto as autoridades europeias afirmaram rapidamente que as entregas continuam normalmente, mas a repetição dos incidentes aumentou a tensão geral.

Ao mesmo tempo, consultorias chamam atenção para os efeitos mais profundos da campanha contra a infraestrutura de refino. Estimativas de mercado indicam que o refino russo, entre setembro e novembro, caiu para cerca de 5 milhões de barris por dia, centenas de milhares abaixo dos níveis do ano passado. A produção de gasolina foi a mais afetada, seguida por cortes significativos na produção de gasóleo. Assim, os riscos se fazem sentir não apenas no petróleo bruto, mas ao longo de toda a cadeia de abastecimento de produtos derivados.

Ainda assim, é importante destacar que a estrutura de abastecimento não está, por ora, desestabilizada. Não há interrupções significativas, e o mercado entende isso: os preços estão subindo de forma modesta, com oscilações de centavos, não de dólares. Trata-se de um exemplo clássico de como a geopolítica adiciona um prêmio de risco pequeno, mas perceptível, sem alterar fundamentalmente os fundamentos do mercado.

Se analisarmos além das notícias de curto prazo, fica mais claro por que os preços do petróleo não estão reagindo de forma tão dramática à geopolítica como em anos anteriores.

Primeiro, o mercado ainda não conseguiu sair de seu estado de excesso de oferta. A produção global está aumentando mais rápido do que a demanda, com algumas regiões exibindo um crescimento particularmente agressivo. A OPEC+ vem tentando equilibrar, há anos, o apoio aos preços com a preservação de sua participação de mercado. No momento, o vetor se desloca claramente para esta última direção: o cartel não está disposto a sacrificar volumes de forma significativa apenas para sustentar preços elevados.

Em segundo lugar, os estoques permanecem confortáveis. Dados recentes dos EUA reforçam esse quadro. Em vez da queda esperada, os estoques comerciais de petróleo bruto aumentaram cerca de 500 mil barris na semana passada, contrariando as previsões de redução feitas pelos analistas. Isso ocorreu mesmo com o aumento da atividade das refinarias: elas estão elevando a produção, mas a oferta disponível é tão abundante que continua a se acumular nos depósitos.

O fato de as reservas estarem subindo mesmo em meio a tensões geopolíticas é um sinal importante: não há escassez física. Para os preços, isso representa um teto — sempre que o Brent se aproxima do limite superior da faixa, mais oferta chega ao mercado, ampliando a disposição para vender e, consequentemente, desacelerando a alta.

Além disso, as avaliações das agências de classificação completam o quadro. A Fitch revisou para baixo suas previsões para os preços do petróleo em 2025–2027, refletindo expectativas persistentes de excesso de oferta e um crescimento da produção que supera a demanda. Já não se trata de um fenômeno pontual: é um cenário cíclico em que o petróleo tende a permanecer sob pressão nos próximos anos.

Nesse cenário, a reação dos mercados de ações dos países do Golfo chama atenção. Para eles, o petróleo é um fator-chave, e até mesmo uma alta modesta nos preços, reforçada pelas expectativas de futuros cortes de juros pelo Fed, tornou-se um forte sinal positivo.

Os mercados da Arábia Saudita, dos Emirados Árabes Unidos e do Catar encerraram a sessão em alta. Os investidores enxergam um apoio duplo: por um lado, preços do petróleo mais altos, ainda que moderados, melhoram a posição fiscal desses países e a lucratividade das empresas de energia; por outro, o afrouxamento da política monetária dos EUA reduz potencialmente o custo do capital, tornando os investimentos nos mercados emergentes mais atraentes.

Os índices regionais são tradicionalmente sensíveis à combinação "petróleo + juros". Quando o petróleo sobe e as expectativas de juros caem, cria-se uma fórmula quase ideal para a entrada de capital no curto prazo. Na prática, isso se traduz em crescimento nos setores de energia e financeiro, com maior interesse por empresas de infraestrutura e indústria ligadas a programas governamentais e exportações.

No entanto, é fundamental entender que esse crescimento ainda se baseia mais em expectativas do que em fatos: o Fed ainda não cortou juros, e os preços do petróleo permanecem dentro de uma faixa. Isso indica que os mercados do Golfo também estão vulneráveis — tanto a possíveis decepções em relação ao Fed quanto a novos sinais de excesso de oferta de petróleo.

O mercado opera hoje dentro de uma configuração singular: de um lado — guerra, sanções, ataques à infraestrutura, declarações políticas e iniciativas de paz paralisadas; de outro — estoques "confortáveis", excesso de oferta antecipado e uma estratégia pragmática da OPEC+ voltada para preservar participação de mercado, não para sustentar preços excepcionalmente elevados.

No passado, um conjunto semelhante de notícias geopolíticas poderia ter impulsionado o petróleo para a faixa de US$ 80–100 por barril. Porém, o ciclo atual é diferente. A economia global desacelera, a transição energética restringe gradualmente o crescimento da demanda e Estados Unidos e outros produtores fora da OPEC+ continuam aumentando a produção, enquanto os mercados se tornam mais racionais na precificação do prêmio de risco.

Guerra e política adicionam alguns dólares por barril, mas não desequilibram o mercado. Sua influência é atenuada pelos níveis de estoque, pelas expectativas de excesso de oferta e pela percepção de que qualquer preço sustentadamente alto estimulará, quase de imediato, um aumento ainda maior da produção.

Olhando para os próximos meses, o cenário base parece ser o seguinte: o petróleo continuará a ser negociado dentro de uma faixa de aproximadamente US$ 60-70 para o Brent, ultrapassando periodicamente os limites superior ou inferior devido a notícias, mas retornando à faixa sob a influência de fatores fundamentais.

Vários fatores contribuem para a manutenção desse cenário:

A situação atual do mercado de petróleo é um exemplo de como os riscos de curto prazo e as tendências de longo prazo convergem para um equilíbrio frágil.

Por um lado, ataques a infraestruturas, interrupções nas negociações de paz e a incerteza geopolítica em geral criam uma demanda contínua por petróleo como elemento de segurança energética e proteção financeira.

Por outro lado, os dados de estoques, as previsões de excesso de oferta e a estratégia da OPEP+ — voltada para a manutenção da participação de mercado — estabelecem um teto para os preços e mantêm o petróleo dentro de uma faixa distante dos extremos vistos em anos anteriores.

Para investidores e empresas, isso significa que a aposta em um aumento acentuado e sustentado nos preços do petróleo agora parece mais fraca do que a aposta em uma maior volatilidade dentro desse corredor e em uma gestão de risco cuidadosa. O petróleo continua sendo um ativo global crucial, mas já não é mais o único centro de gravidade do mercado mundial, está se tornando cada vez mais uma das variáveis de uma equação mais complexa, em que as taxas de juros, a dinâmica econômica global e a transição energética desempenham papéis cada vez mais importantes.

LINKS RÁPIDOS